It was a big day on March 12, 2018, in Cary, North Carolina, as Epic Games geared up for its next big announcement: Fortnite was coming to mobile. The battle royale title had grown significantly over the preceding months, transforming Epic into one of the biggest companies in the world.

The mobile launch added another layer to that rise and tapped into a larger audience than many PC or console games had lured in. The cultural phenomenon became apparent and Fortnite soon landed merchandising, music, and film collaborations, from hosting rapper Travis Scott for a virtual concert after the start of the coronavirus pandemic to premiering a sneak peak of the latest Star Wars movie.

Now, Epic is gearing up for a legal battle against the most valuable company in the world and is making a must-see event out of it.

Epic is seeking a very minor legal win for itself: the restoration of Fortnite to Apple’s App Store after it was booted in August 2020, with the court-approved inclusion of a payment system built by the developer and not Apple. But the precedent set at the end of this trial could spell bigger problems for Apple as Epic asks for the court to deem its practices and commission structure unlawful. That would be a huge win for other developers and for antitrust prosecutors at large.

Apple also remains under investigation by the United States government, which has already brought cases against two other major tech companies and is likely to do the same against the iOS developer. Congress’ focus on Apple is broader than the Epic case, but one issue is the same: how much revenue Apple takes from people who sell on its platform.

Epic’s primary qualm with Apple focuses around the 30 percent commission it takes from publishers on the App Store. While Fortnite is free to play, Apple takes that cut if users purchase in-game currency for cosmetic items while playing on their iPhones or iPads. Epic voiced its public frustration last summer and then it took action.

In August, Epic purposely violated Apple’s developer agreement. The developer launched an Epic-made in-app payment system that skirted those rules. Fortnite was swiftly kicked off the App Store and within 24 hours, Epic filed suit.

Epic is not the first developer to take issue with Apple over its 30 percent cut. Match Group—the parent of Tinder, Match.com, and OkCupid—spoke out against Apple in 2020. Spotify, Apple’s largest competitor in the music streaming space, has also accused Apple of being anticompetitive. Spotify’s allegations have sparked an expected criminal case against Apple in the European Union.

Given its very deliberate timing though, Epic has the chance to make a significantly larger impact. This is not just Epic Games v. Apple. It’s a swarm of app developers, large and small, and one of the most powerful governments in the world versus one of the world’s biggest companies.

If the court rules in Epic’s favor, decides Apple’s policies are anticompetitive and unlawful, and that decision holds up through inevitable appeals, it will be a watershed moment for app developers everywhere. It will also establish legal precedent the U.S. government will draw on in its own case against Apple.

“Right now I think a lot of people would say Apple being big is not the problem,” Michael Arin, an antitrust attorney who works as an editor-in-chief of the Esports Bar Association Journal, told Dot Esports. “It’s when you start looking at all of the users of the iPhone that depend solely on the App Store to have programs. You have to start questioning what Apple is doing with that store. Is it allowing free competition or is it putting its thumb on the scale?”

Congress first began investigating Apple, alongside Facebook, Google, and Amazon, for antitrust concerns in June 2019. The governmental body accused the four companies and their top executives of being modern-day robber barons and monopolists, stomping out competitors by acquisition or platform suppression and holding too much power across the internet.

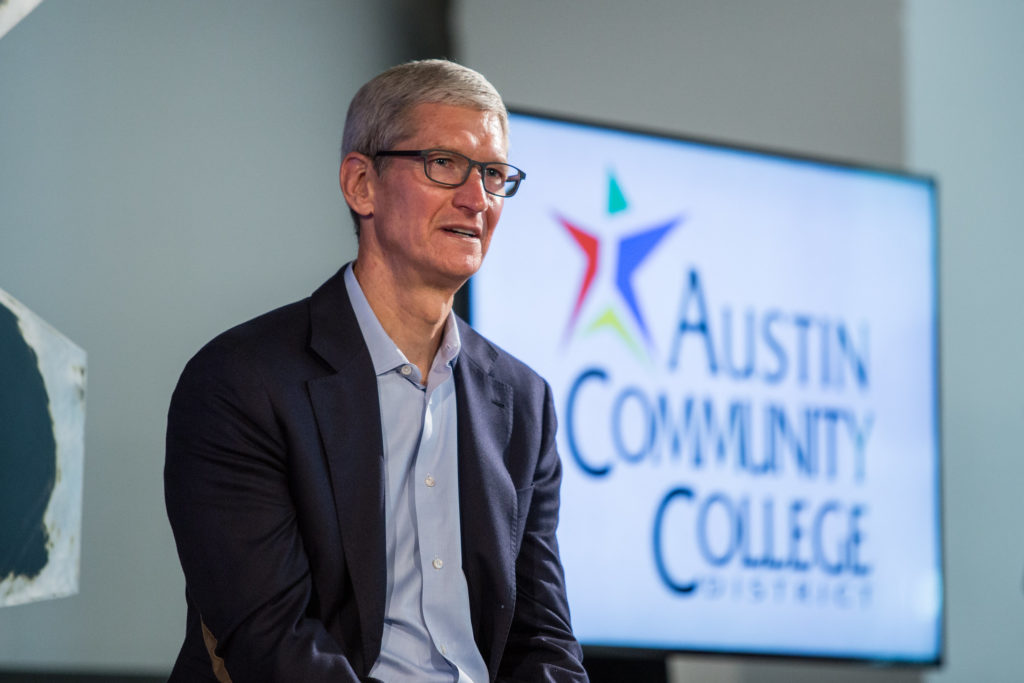

During that investigation, it called Apple CEO Tim Cook, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, Amazon chairman Jeff Bezos, and Google CEO Sundar Pichai for a day of interviews in July 2020—where many representatives in a bipartisan group grilled the four companies’ top brass. A few months later in October 2020, Congress released a 450-page report eviscerating the four companies and echoing much of the closing sentiment of those July 2020 interviews.

“When [the antitrust] laws were written, the monopolists were men named Rockefeller and Carnegie,” committee chair Rep. David Cicilline (D-RI) told the four executives. “Their control of the marketplace allowed them to do whatever it took to crush independent businesses and expand their own power. The names have changed, the story is the same. Today the men are named Zuckerberg, Cook, Pichai and Bezos.”

U.S. federal government bodies, including the FTC and the Justice Department, have already filed suit against Facebook and Google. It’s only a matter of time before Apple and Amazon are on the chopping block too.

Collectively, the current and impending lawsuits could equal some of the biggest antitrust prosecutions in history and certainly the largest in modern internet and tech companies. It’s been 20 years since the U.S. government brought its landmark case against Microsoft, which the government successfully won even through appeals and broke up the tech giant.

In an interview with NPR, Epic CEO Tim Sweeney claimed Epic’s timing to provoke Apple did not center around the government antitrust probe. But the civil suit between Epic and Apple will ultimately impact the likely impending government-prosecuted case.

Unlike the U.S. government though, Epic’s playbook around the lawsuit was anything but traditional. It successfully turned something rather mundane—antitrust law—into a spectacle.

After it filed suit in August, Epic released a parody commercial mocking Apple’s famous 1984 Super Bowl commercial where it attacked IBM, the then largest maker of personal computers. Epic’s version featured an apple-headed character, which it of course released as a Fortnite skin shortly thereafter. In a coordinated marketing and public relations campaign, dubbed Project Liberty internally, Epic drummed up interest not just in Fortnite but in sticking it to Apple in a way that no other company has done successfully.

“I was astounded. Not because of the legal case itself but because of Epic’s take on how to make a legal case, which is usually a dead boring matter, into a social phenomenon,” Arin said. “Epic came out swinging and swinging hard.”

Along the way, Epic sold itself as fighting for the little guy. Epic represents a much larger cause and frustration for many app developers, but it is by no means a small company. Epic is a founding partner of Coalition for App Fairness, which includes Spotify, Match Group, Basecamp, and some other larger tech companies. Each has a bone to pick with Apple, and through coordinated publicity campaigns and government complaints globally, members of the coalition seek to knock down the 30 percent “app tax,” as they call it.

Fortnite’s rocket ship-level growth in popularity catapulted Epic into the list of the most valuable privately-owned game companies in the world. In April, Epic completed a fundraising round that saw it valued at $28.7 billion (Apple is worth $2.21 trillion, as of Friday). Epic is not exactly the little guy anymore and no true little guy would be able to fight Apple like this.

Some of its partners are, though. Epic has formed a special relationship with many indie app developers, stemming from its innovation on the 88-12 revenue share model on the Epic Games Store. That policy’s done a lot of good, and Epic’s also waived Unreal Engine royalty cost for people who publish on its platform. Some of those developers cross publish onto iOS too.

“Our costs of offering the store, processing payments, supporting customers and providing bandwidth for download is between 5% and 7%,” Sweeney told Protocol. “That’s the cost of operating an app store, and we’re not at nearly the economies of scale as Apple and Google, so their costs are likely lower.

“To say that the fact that they have some costs justifies taking 30% of a company’s revenue and preventing other companies from competing with them is absolutely abhorrent.”

On Thursday, Microsoft announced that beginning Aug. 1, it’d mirror Epic’s revenue share model for PC game publishers selling on the Microsoft Store. Apple too has made changes since the Epic suit last year, with the fee lowering from 30 percent to 15 percent for any developer making under $1 million in sales per year. Other cases have popped up challenging other markets too, like Valve which is being legally challenged for its 30 percent cut on games on its platforms.

Epic’s efforts against Apple have already made a dent, but it will continue in court. The case will feature testimonies from a large group of some of the most powerful people in tech and games. Both Cook and Sweeney will testify and so will many of Apple and Epic’s top brass. Microsoft vice president of Xbox business development Lori Wright will take the stand, as well as several expert academics from UCLA, MIT, and New York University.

New documents from Google and Roblox will be featured, too, to contrast with Apple’s policies around publishing.

To say that the fact that they have some costs justifies taking 30% of a company’s revenue and preventing other companies from competing with them is absolutely abhorrent.

— Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney to Protocol

At its core, Apple’s defense centers around security and market standards. It says allowing third-party payment processors, like the one Fortnite implemented prior to being booted off the App Store, opens up vulnerabilities. Apple also argues against sideloading, the ability to install apps from third-party sources, a common and legal practice on Android devices—but one that’s been barred by iOS from day one.

“Users aren’t going to come there and buy things if they don’t have trust and confidence in the store,” Cook told New York Times columnist Kara Swisher in a podcast interview in late March. “And we think our users want that. If you had sideloading, you would break the privacy and security model.”

Apple said in its pre-court filings the rest of the market shows why its practices are fair. In an April 7 filing, it cited Microsoft’s revenue share model with Xbox since 2005 and Sony and Nintendo with the PlayStation Store and the Wii Shop Channel since 2006, all three which see the storefront take a 30 percent cut. Microsoft’s announcement just days before the trial marks an interesting twist—a knife to Apple’s back to erode its argument.

All-in-all, Apple needs to argue iOS is not distinct from those other platforms. But in part, it has to fight against itself too. Apple’s own other platform, MacOS, doesn’t hold the same standards as iOS. Apple’s reputation for security is equal on both platforms, even though Macs allow for various third-party applications to be used, many off of the App Store. There, Steam, Origin, and even Epic Games Store are allowed to exist and download other programs as long as they meet certain security requirements.

Apple has been the target of several antitrust cases before. There’s Apple v. Pepper, another case from 2018 to 2019 that centered around the consumer’s right to pursue Apple in class action lawsuits for anticompetitive practices. The Supreme Court ruled narrowly in the consumer’s favor, which allowed for them to collectively sue Apple or others in future cases. Then there’s the United States v. Apple the first time, which accused Apple of price fixing ebooks. The New York court found Apple guilty of that too. Those two cases existed mostly in a vacuum—without extenuating circumstances and additional probes into Apple—while the Epic case does not.

At its core, Epic is voicing a concern long held by many but often too financially steep in court fees to overcome. It sensed a weakness for Apple, under fire from other developers and from the U.S. government, and it’s capitalizing on the moment. Congress isn’t the only one paying attention either. On Thursday, Reuters reported that the European Union antitrust regulators are expected to charge Apple with anticompetitive conduct following a complaint from Spotify, who are based in Sweden. If found guilty, Apple stands to lose up to 10 percent of its global revenue in that case.

When asked by Swisher in that March interview about the App Store policies being a vulnerability for Apple, Cook deflected. He said the pros of the App Store and its financial benefit to entrepreneurs around the world—turning small companies into quite successful ones because of app sales—outweighed Apple’s “very small sliver” of a commission. But Cook also pointed to the App Store’s evolution in policy and its recent commission decrease for smaller developers as a sign the company would make reforms as needed.

Fortnite still remains off the App Store. In pre-trial filings, Epic failed to convince the court to reinstate it before all sides were heard—and the judge said its removal was self-inflicted, as Epic knowingly violated Apple’s policies. That same court, however, also barred Apple from revoking Epic’s iOS developer license, citing the harm it would cause to other Unreal Engine games made for the iPhone.

Monday is the beginning of what’s expected to be a very contentious trial. It’s full of high-profile witnesses and testimonies and it’s the beginning of a war Apple will need to continue to fight even after this case. Neither Apple or Epic are coming into trial with a leg up, but how the ensuing months play out will mean a whole lot to the future of app development.

Make sure to follow us on YouTube for more esports news and analysis.

Published: May 1, 2021 04:11 pm