This was the year. If there was a time a Western team could win the League of Legends World Championship, 2021 was it. Ten years have passed since Fnatic won the first edition of the tournament. That means it’s been 10 years since the last European champion, while American organizations are still pursuing that elusive title.

Then, unexpectedly, a boon came when Worlds was suddenly moved from Chinese to European soil. And this year’s Western representatives boasted some of the best talent we’ve ever seen—perennial superteams like G2 Esports and TSM failed to even make it out of their regions.

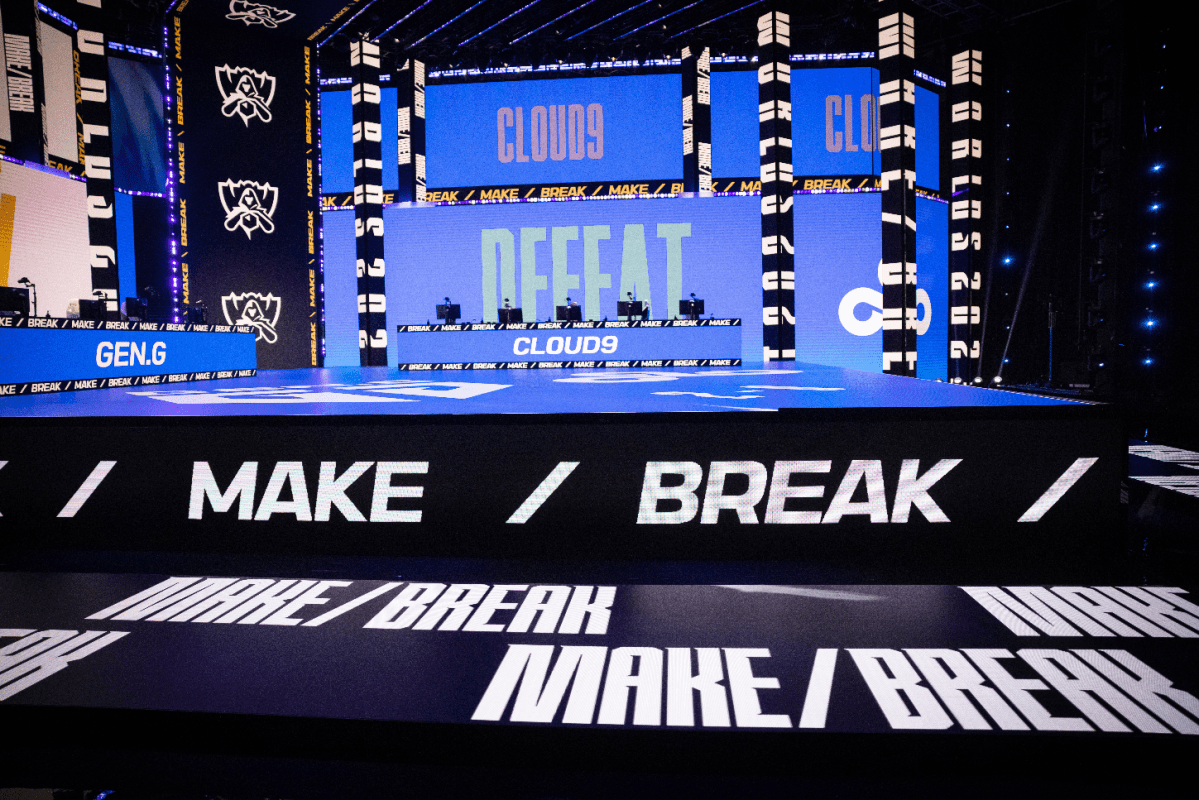

Instead, this year turned into the worst Worlds ever for the West. Only two teams—the LCS’ Cloud9 and the LEC’s MAD Lions—made the quarterfinals. Even that result required some luck and gutsy play in the second half of the group stage when C9 came back from a 0-3 record to somehow advance with a losing record. But in the quarters, neither team mustered a single game win against superior competition from Korea.

Afterward, there seemed to be a sense of resignation from the community over the hard-stuck LCS and LEC teams. C9 coach Mithy talked about how his team’s inability to practice against Chinese and Korean competition set his players back. Overall, the sentiment has shifted from “if we fix this, we can succeed” to “the system is broken, we are doomed.”

That may be the case, but not necessarily for the reasons Mithy described.

You are what you eat

In the middle of the group stage, former LCS coach Zaboutine tweeted the records of each region along with a point: “You’re only as good as your ladder is.” The numbers—the LPL at 10-2 and the LCK at 8-4—weren’t surprising. Going into Worlds, everyone expected those regions to dominate. But the part about each region’s solo queue ladder forming the foundation for their teams’ performance was interesting.

Solo queue is a controversial part of the League ecosystem. It’s great for competitive gamers, but it can be a frustrating experience due to high ping, long queue times, dodges, mismatched Match Making Rating (MMR), toxicity, and numerous other issues. But it’s also an essential practice tool for pros, who often train as much on their own climbing the ladder each day as they do in organized scrims with their teams.

The list of solo queue frustrations isn’t shared by each region equally. Because of population density, geography, and infrastructure investment, South Korea has an extremely low ping environment. And decades of building gaming and esports in that nation has led to a huge number of players competing on the solo queue ladder. China makes up for its shortcomings in ping and geography with the game’s biggest player base. Four years ago, Riot Games even started an elite-players-only server because there were so many players ranked Diamond or higher.

In NA specifically, the top of the ladder isn’t just about competition. Many of the region’s best players are streamers for whom winning and grinding LP isn’t their focus. They’re skilled—many are former pro players—but as content creators, they don’t always have the competitive mentality or consistency to push the gameplay higher in the region. That simply isn’t their job anymore. And the size of both the European and North American servers is dwarfed by League’s Chinese player base. When you have more players in the pool, it takes more talent and effort to make it to the very top.

That’s one reason why a common solution—importing talent from other regions—hasn’t worked. You can bring them over, but you can’t bring their ladder.

You learn what you can see

The poor quality of the ladder doesn’t just impair the players, it affects the ability of coaches and analysts to prepare their teams. When asked how much the quality of the ladder impacted the quality of North American teams, one veteran LCS and Academy coach told Dot Esports “a lot.”

When the solo queue environment isn’t challenging, a lot of the best players settle on the same champions and tactics. Things like top lane Jayce—a staple in Korea—and Ziggs as an answer to poke bot lanes aren’t played as much by Western teams. They aren’t learning or innovating. Playing more games would help, but it wouldn’t fully fix that problem. In a lot of cases, these teams rely on Pro View, in-house practice, and other data tools to learn. That comes with its own set of challenges: Players can use Pro View to see how their peers in other regions play certain matchups, but they can’t get firsthand insight by trying them out for themselves. And while data tools can give them insight into the preparation that led to those matchups being revealed on stage, they can’t ever learn what it was like to actually research those interactions.

Several coaches and analysts pointed to in-house play as a way for the West to catch up. But the system has generated a fair amount of, well, discord over the last two years. This isn’t to say that in-houses aren’t a potential solution, just that they’re still in an early stage of development where schedules are inconsistent and queue times are long. And given that in-houses are still contained practice within the same region, one coach pointed to Pro View as a superior tool anyway.

That’s why simply boot camping in Korea or China, as Mithy indicated, isn’t the full answer. Coaching and scrimming are important, but a lot of development happens when pros go against talented amateurs in unstructured solo queue practice. It’s not a quick exercise—in fact, it could take years before results manifest.

The proof is in the rosters

The problem of ladder quality and a lack of amateur development is more distinct in North America than it is in Europe. After all, this year’s European squads notably lacked a single LPL or LCK import. And European teams are typically fine at Worlds—we’re just two years removed from two straight Worlds finals featuring an EU team. It might just be a blip of bad luck, but it’s not encouraging that with Worlds in Europe and having pre-tournament scrims happen on home turf, European squads still couldn’t stand against the years of training their Asian counterparts enjoyed practicing against stiff solo queue competition.

Another great example is the historic performance of VCS teams at Worlds. It’s unfortunate that they’ve missed the last two tournaments due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but Vietnamese players would often connect to the Korean server, even at enormously high ping, to grind against the best LCK and LPL pros. And it seems like every tournament, they’d bring with them some surprising cheese strategy to turn things on their head.

But the best case for how a ladder can shape a champion can be seen in the best team of all time, one that returned in the semifinals of Worlds: T1.

Despite being the winningest team in the history of both the LCK and Worlds, T1 has never been afraid to shake up its roster. Perhaps that comes from trusting a bespectacled teenager in 2013 to be the face of the franchise. Whatever the genesis, year after year, T1 makes bold, unexpected moves to reshape its roster. And the players it’s replacing aren’t even bad—the semifinals were peppered with former T1 acolytes, from Gen.G jungler Clid to DWG KIA top laner Khan and EDG mid laner Scout. You could probably win Worlds with a roster of only players T1 has kicked.

In the places of those respected pros, T1 fielded a Worlds roster with a bevy of new faces. Canna was signed as a teenager to replace Khan. Oner still is a teenager, one who almost took down Canyon, the then reigning jungle champ, in the semifinals. But neither might be as good as Gumayusi, who forced his team to sit Teddy, a legendary player himself. Some say that Gumayusi is part of the best bot lane in the world.

True or not, T1 almost went all the way with Gumayusi leading the charge, falling in five breathtaking games to DWG KIA in the semifinals. It’s an opportunity they never would have had if not for the strength of the Korean ladder.

Make sure to follow us on YouTube for more esports news and analysis.

Published: Nov 10, 2021 04:54 pm