On a late December night in 2017, Joshua Ackerman stood on his porch looking at a pair of cars that just pulled into his driveway.

A man emerged from one of the vehicles and handed him a set of documents.

“You’ve been served,” the mysterious figure said.

For the past two years, Ackerman had been embroiled in a cross-state dispute with his ex-wife over their two-year-old son. The two hadn’t legally ironed out custody. And as Ackerman stood outside on that frigid evening, he saw his ex-wife sitting in the backseat of one of the cars parked in front of his house.

He looked down at the documents. “Emergency Injunction to Set Custody,” one read, issued by the “Family Court of Hamilton County” from Tennessee, where his ex-wife lived. They made no sense, as Ackerman and his ex-wife’s custody battle hadn’t escalated this far. And none of the proceedings had even taken place in Tennessee. Several months earlier, Ackerman had moved their son in with him and his new fiancée in North Carolina.

As he continued to read the documents, another man, dark haired and heavyset, stepped out from one of the two vehicles. He introduced himself as Joshua Mullins, an attorney representing Ackerman’s ex-wife. If Ackerman didn’t turn over his son immediately, the lawyer threatened, he’d be charged with kidnapping.

Ackerman refused.

Once the group left, Ackerman drove to his parents and notified his lawyer. The investigation that would spring from this phone call, ultimately led by financial crime detective Jeff Bryden in Chattanooga, Tennessee, would stretch across three states and involve four crimes.

In reality, there was no “Family Court of Hamilton County.” The documents were fake. Ackerman’s ex-wife had been duped. And she wasn’t alone.

Bryden shortly became aware of several other cases involving Mullins. He’d purchased an Audi A5 with a fake check several weeks earlier. He’d also fraudulently opened and then purposely attempted to overdraw a number of bank accounts with two financial institutions in Tennessee and Virginia. But before he dabbled in cars and child custody cases, Mullins got his start in a young, booming industry that had started to attract big time investors—and scammers.

Realizing what was on his hands, Bryden got excited.

“I was looking forward to meeting him,” Bryden told Dot Esports. “When I worked the case, I called it the Catch Me If You Can case. It reminds me of all that stuff that kid was pulling off.”

In many ways, Mullins really did seem like another Frank Abagnale, the young master forger who impersonated doctors, lawyers, and pilots and was later portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio in the hit movie. Abagnale was meticulously tracked by the FBI throughout his criminal escapades. But Mullins, until this point, had never run into trouble with the law. And yet Bryden had just scratched the surface.

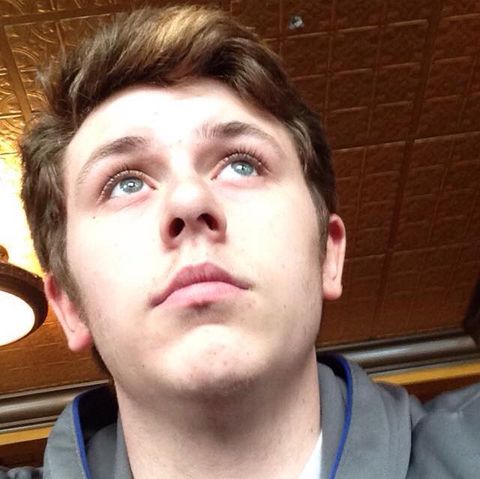

For years, Mullins is alleged to have run a number of schemes in esports—forging checks and bank documents, selling himself as a multi-billionaire investor, and attempting to defraud teams, leagues, and players. Several of his past associates and business partners allege that Mullins attempted to take $42 million from them during his time in esports. And it was all between his fifteenth and eighteenth birthdays.

Since late 2015, hundreds of investors have flocked into esports. They’ve spent billions attempting to capitalize on the next big thing. Mullins sold himself off as just another rich kid with a lot of money to throw into a rapidly expanding industry. There was, to a certain extent, nothing unusual about him. And he didn’t take no for an answer. He was determined to break into the industry, no matter who he hurt or scammed along the way.

Born on New Year’s Day, 2000, Mullins relocated around the southern U.S. until his family of six settled in small towns in the North Georgia Mountains in 2012. He told people he attended Woodward Academy, one of Georgia’s most prestigious private schools, but he was actually homeschooled, according to a number of social media posts he made at the time. He wrote books as a 12-year-old kid and filmed amateur music videos to hit pop music.

As a young teenager, Mullins threw himself into the internet, creating a Facebook profile after his eleventh birthday and connecting with strangers from around the world. He took to coding and software. He got into Minecraft. By the summer of 2015, Mullins started an internet services company that helped build custom Minecraft servers. It was through this work that he eventually met another teen with big business ambitions: Joey Amoruso.

Amoruso, a few months younger than Mullins, grew up in Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania, a suburb outside of Pittsburgh. Like Mullins, he almost lived online. The two became fast friends and after some discussion, Mullins offered to hire Amoruso to work for him.

“So bad news, I guess. Riot approves. Welcome to the Challenger Series.”

– Joey Amoruso, 15, who became one of Mullins’ closest business partners

Amoruso accepted, but at that point, he was already deep in a business of his own. In early 2016, he and a friend took over Volume Gaming, an amateur esports team.

Amoruso and his friend, an 18-year-old from Brantford, Ontario, Canada, named Kole Money-Melissen, ran Volume modestly. The two didn’t have much money, other than their allowances and odd jobs. But they had a passion for the industry. At any point, Volume represented three-to-four teams with little-to-no salary. The two were proudly a part of the amateur scene—until Amoruso saw an opportunity.

In May 2016, Team Dragon Knights, which had once been a top team in North America, was on the open market, forced to auction off their League of Legends Challenger Series spot by Riot Games.

Amoruso contacted brothers Chris and Sean Shim, the team’s founders, to strike a deal. He offered them $340,000 for the slot and several player contracts, a figure other organizations participating at that level of pro League said was far above market average at the time.

The Shims accepted, and Amoruso tried to figure out how to make it work. He even brazenly contacted one of the reporters for this piece, a journalist at ESPN at the time, to request press coverage. Ultimately, Amoruso realized there was no way they’d be able to fund it; he was a 15-year-old high school student and Money-Melissen worked at a local McDonald’s in his hometown.

But that didn’t stop him from trying.

In a series of text messages over Skype provided to Dot Esports and verified by Money-Melissen, Amoruso suggested they forge a bank notice and have one of Amoruso’s school friends pose as an investor in a phone call with the Shims.

“We’ve come this far, why stop now?” Amoruso wrote.

“It’s a huge risk and a high reward,” Money-Melissen replied.

“But could also end up with us being in court sometime.”

Amoruso sent another message to Money-Melissen the next day. It had worked.

“So bad news, I guess. Riot approves. Welcome to the Challenger Series.”

The deal fell through, Money-Melissen said, when he refused to sign the final contract in fear of legal ramifications. TDK sold the Challenger Series slot to another organization a few days later. Amoruso and Money-Melissen stopped speaking after the TDK deal fell through.

“[We had] a falling out; it lasted about four months,” Money-Melissen told Dot Esports. “He sat me down, apologized, and said it was a one-off thing and that we should try again, take it slow and do it the right way.

“I agreed.”

Mullins wasn’t always involved in esports, but his gaming interests led him to form a close personal bond with Amoruso. As they worked together through late 2015 and early 2016 on the software company, Amoruso told his counterpart about his esports endeavors. Mullins, who’d said he was a wealthy investor in their conversations, claimed he’d invest “if the opportunity was right.”

“He told me his ‘family’ story of his mom being an exec at a Fortune 500 company,” Amoruso told Dot Esports. “I don’t remember which one but [what] I [saw] at the time [on] his mom’s LinkedIn page, that made sense with what he said.”

The idea of a small-name team backed by a wealthy but little-known investor wasn’t unheard of at the time. Esports was, and still is to many, something of a gold rush opportunity—the next big thing in sports with potential for astronomical returns. For a brief period, roughly from 2015 to 2017, business and sports moguls took especially speculative risks in hopes to break into the pro scene.

One set of investors launched Ember, an amateur team that spent heavy amounts of cash in an attempt to break into pro League of Legends, only to fail to even qualify for the promotion tournament. Another amateur venture, Odyssey Gaming, was backed by Martin Shkreli, the pharmaceutical executive and convicted felon who infamously jacked up the price of a key AIDS medication. Shkreli would later leave the industry indebted to some players and staff. Teams like Volume got scooped up, loaded with cash, and handed to inexperienced operators, often just gamers with at most a modicum of business experience.

Big names with unquestionable financial resources also were entering the space at the time: Mark Cuban, Shaquille O’Neal, Rick Fox. But so did the children loaded with their parents’ money. Mullins’ background hardly seemed unusual in the space.

Together, Mullins, Amoruso and Money-Melissen formed an unlikely trio in 2016. Money-Melissen, then 18, would sign the majority of their documents. Amoruso would take the lead on the business. And Mullins, with his self-proclaimed deep pockets, would fund them.

Through the latter half of 2016, the trio offered esports teams funding from a few hundred thousand dollars to upwards of $40 million, according to offer sheets and contracts penned by Mullins and obtained by Dot. To obtain the funding, these teams would need to put their own money into either American Express or Bank of America escrow accounts owned by Mullins, according to the documents. In other words, Amoruso and Mullins were promising to give out big-time funding—but only if, unbelievably, the teams paid them a deposit first.

The group tried this scheme at least three times: once with Team Sky, a North American amateur League of Legends organization; again with Rogue, then a professional Overwatch team; and lastly with Michael Schnorr, an independent League of Legends manager who had worked with pro teams in the past.

When Schnorr began speaking to the trio, he did some outreach to colleagues across the industry. He saw that Frank Villarreal, the Rogue co-founder and CEO, followed Mullins and co. on Twitter.

Schnorr messaged Villarreal on Christmas Day 2016. “As I’m about to start working with [Mullins], I was wondering if you could vouch for him?” Schnorr asked Villarreal.

“They’re scammers,” Villarreal replied, “stay away.”

Villarreal explained the scheme—how Mullins, Amoruso and Money-Melissen’s company offered them a private jet and funding, but that they’d need to deposit collateral into an escrow account. “We’d have to put [in] $250,000… and they’d steal it,” Villarreal said.

Schnorr ended his working relationship with them. The three never got a dime out of Rogue or Schnorr. But a document shows they tried the same scheme with Sky, offering a $40 million investment if a deposit was made. That was unsuccessful, too, Money-Melissen said.

With that scam going bust, the three were still desperate to get into League of Legends. So they hired a consultant, former Immortals team manager Elliott Smith. He had both the résumé and connections to get them an audience with top executives in the space. Money-Melissen paid Smith a small fee out of his own pocket.

In September 2016, Smith found their in.

With a rule change to sister teams of pro-level organizations, Team Liquid put its Challenger Series slot up for sale. Smith got in touch with Liquid co-CEO Steve Arhancet and explained that the group could pay $75,000 for the slot. Mullins then sent a document written by Slayde Global Bank, which claimed to be a partner of Goldman Sachs, that said his company had $330,000 in deposit.

Mullins frequently sent bank documents like this with noted balances on them. Throughout 2016, he issued documents that were addressed to potential partners from or claiming association with Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, Everbank, Bank of America, and American Express, each of which were obtained by Dot Esports.

As the process continued with Liquid, Smith grew suspicious. He felt that Mullins embellished his wealth, that he never gave a straight answer when asked about his money. With his personal reputation on the line, Smith secretly wrote an email to Arhancet in early October 2016.

“I wanted to let you know that we will not be able to transfer the funds by the deadline,” Smith wrote. “It is probably best that you find another buyer. I personally cannot in good faith give you the illusion that we are established enough for this not to be risky for you.”

Team Liquid sold the slot to another organization days later. Arhancet declined to comment for this story.

The whole process left Smith skeptical, particularly about Mullins. He warned Amoruso and Money-Melissen, he told Dot Esports.

“On multiple occasions, [I] advised [them] to pull out,” Smith said. “But as they refused to do so, we felt the urge to try our best to help these kids to the best of our ability, advising them to seek legal counsel and working to help them with budgetary planning and negotiations.”

Frustrated with one another again, Money-Melissen and Amoruso had another falling out. They didn’t speak for several months and the schemes stopped.

Outside of esports, Mullins encountered his first run-in with the law. In early 2017, Georgia prosecutors charged him with battery. He was 17. Authorities said he tied his mother’s left arm up and held her hostage after a family dispute. A month later, he pled guilty to a misdemeanor charge. The court sentenced him to a year’s probation and fined him $680.

“We all want to do this for the rest of our lives. We want to make this our full-time job, but at the same time, you have to be smart about it. That was unacceptable: I was not smart about it as I should have been.”

Levi Collins, an esports executive who Amoruso offered a $250,000 salary

As the three laid low for a few months, the esports industry underwent significant changes. Riot Games began a year-long process in 2017 to move away from a promotion-relegation model for the League Championship Series and pivot into a franchised model with permanent teams. Entering that league would cost $13 million for a new investor.

It wasn’t long before Amoruso and Money-Melissen reconciled. They wanted to be a part of this new league.

The duo created a 30-page document outlining their experience in esports, discussing their financial budgets and goals and their plan to create a successful team. They called it Draco eSports and estimated it’d cost $43 million to operate over the course of five years.

Their investor for the project? Mullins, of course.

The franchise application document followed the frameworks laid out by Riot Games to a T—but a representative from Riot told us they never received it. That didn’t stop Amoruso and Mullins from telling people they’d be a part of the LCS though.

To build some credibility in the space, the three proposed they’d merge with another amateur organization, EMP, and that its top executive, Levi Collins, would work for them. They offered Collins a $250,000 per year salary. He could leave his full-time job in manufacturing and finally pursue esports as his main gig. Amoruso told Collins the news that they were a part of the LCS.

“He showed me all of the documents,” Collins said. “He showed me plans of an office being built in Los Angeles. Then he went over all of these things, like sponsors, some people they were looking to acquire, the people at Riot Games he was talking to; that was really it.”

Draco launched big in late October 2017. They signed a Call of Duty team, led by veteran pro Steven “Diabolic” Rivero. Their sponsors, according to their Twitter account, included Nike and DXRacer.

As part of their announcement, Amoruso posted a video to the company’s Twitter account. It featured the then 17-year-old in a conference room, dressed in an oversized suit, as he began to lay out their plan. He never mentioned the LCS slot (Riot itself wouldn’t announce the league’s new teams until weeks later) but he spoke at length about the Call of Duty team and the other players they’d be adding to the roster, like Super Smash Bros. pro Chris “WaDi” Boston.

Collins felt elated. Finally, after all this time, he had made it in esports.

But the video was actually Draco’s downfall.

The publicity from the launch drew the type of attention the group weren’t accustomed to. The whole situation seemed noticeably off—how could a brand new team procure such high-profile sponsors? How could their CEO possibly be so young? And where did the money come from?

Online viewers quickly started unraveling Amoruso’s past and pulling apart the lie. An internet sleuth named Elle Thibeau published a document with screenshots of conversations where Amoruso misled past business associates, both with Volume and Draco.

DXRacer messaged Collins asking for proof of a deal between Draco and the chair manufacturer. He had no response. A representative from Nike told Dot Esports that the company wasn’t familiar with Draco, and certainly hadn’t sponsored the organization. Before long, Collins found himself at the center of a flurry of messages and online comments accusing him of fraud.

Amoruso disappeared from social media and Collins, unaware of how it all came to be, was held responsible. On Oct. 30, 2017, he started a Periscope stream on his personal Twitter account. He was crying—well aware at this point that he’d been scammed by a trio of fraudsters.

“This opportunity that was presented to me, you never know, and that’s what I kind of took it as,” Collins said. “We all want to do this for the rest of our lives. We want to make this our full-time job, but at the same time, you have to be smart about it. That was unacceptable: I was not smart about it as I should have been.”

Collins tried to resurrect his previous organization but the damage was done, both to the organization’s reputation and to his own passion for running a team. He shut it down and exited the esports industry a few months later in March 2018.

Perhaps feeling guilty for what he took part in, Money-Melissen for the first time responded to our inquiries. He described the schemes he’d been party to. He claimed he never knew Mullins was a con man and he said his conversations with Amoruso since that October 2017 meltdown had been minimal and informal, touching only on small talk.

As part of these conversations, Money-Melissen provided Dot Esports with documents that laid out almost everything, including ones where Mullins claimed to be a lawyer and financier. Money-Melissen shared pictures of checks Mullins wrote to him and others, as well as the financial documents he sent to Liquid and their other targets. Those checks, he said, terrified him. He feared that if he attempted to cash them, he’d be arrested on the spot.

Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs confirmed to Dot Esports that the documents bearing their names were fake. (Everbank declined to comment, and Bank of America and American Express did not respond to requests for comment.)

Mullins has never spoken about his time in esports, but he did curiously write Smith, the consultant they hired, an unprompted letter in February 2018.

“I am contacting you today to inform and discharge all of my misrepresentations that were made to you and [your company],” Mullins wrote. “I am not associated with and never have been associated with Goldman Sachs Bank, N.A., or the Goldman Sachs mark.”

Since sending that letter, Mullins pleaded guilty to felony forgery in Cobb County, Georgia, in January 2019. He’d fabricated a legal settlement with signatures from a local law firm and attempted to use that document as collateral for a new loan, court records show. Mullins was sentenced to 10 years probation and a $1,000 fine, being charged as a first-time adult offender in Georgia.

But in two other counties, Hamilton County, Tennessee, and Gilmer County, Georgia, Mullins is indicted on 43 other counts of identity theft, forgery, and the impersonation of a lawyer.

On his now-deleted LinkedIn page, Mullins said he was a graduate of Stanford and an alumni of Georgetown University’s law school. Both universities say he doesn’t appear in any of their records. Mullins also claimed to have worked for the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and Alphabet, the parent of Google. Neither company ever employed him, according to a BCBS Association spokesperson and a Google source.

Amoruso, for his part, says he’s yet another victim of Mullins, that he never knowingly misled or scammed anyone in esports. The Nike and DXRacer partnerships, he said, were presented to him by a third party whose name he claimed he could no longer recall. He stopped responding to inquiries after an initial text conversation in which he refused to speak on the phone.

To a certain extent, their story encapsulates another era of esports, its wild early days—before the billionaires, before the big money. It was an era where teams like Denial Esports, who won the 2015 Call of Duty World Championship, exited the industry two years later with debts to former players totaling more than $35,000. One where a man with no event experience coaxed top Counter-Strike teams to compete in his tournament in Slovenia in 2015, before he blew through his budget and failed to pay the $50,000 in prizes owed.

Mullins also entered at what could have been the perfect time, as this old esports world was starting to draw the attention of people with real financial muscle. Fearful they might miss out, major investors took risks, even if it meant partnering with questionable figures. After early 2018, Amoruso and Money-Melissen moved on from esports. Amoruso now calls Draco a “mistake.” And yet, what the three nearly accomplished, in such a short time, is stunning. Three teens with little more than a skill at forgery nearly broke into the top of the esports world.

Mullins, the financial mastermind, has resided at the Gilmer County Detention Center in north Georgia for more than a year. His trial remains delayed due to coronavirus restrictions. Inquiries to his lawyer and letters sent to the jail by Dot Esports were not responded to.

Once an ambitious and talented kid who almost pulled off one of the biggest scams in the history of esports, Mullins’ time in the industry is now mostly forgotten.

“I talk to all kinds of people and he was a smart kid,” Bryden, the detective whose investigation led to Mullins’ 2018 arrest, said. “In my opinion, he could’ve done whatever he wanted to do.”

Hendley & Goodwyn, LLP, a Tennessee-based law firm, assisted with public records requests for this story.