Franchising seems imminent in professional League of Legends, but it’s not the real issue affecting league stability. News broke recently that publisher Riot Games was seriously considering a franchise model for the North American League Championships Series, possibly beginning in 2018. Next came the news that China’s League of Legends Pro League was skipping ahead and ending relegations this summer. There are many good arguments for franchising, as Dot Esports contributor Harris Peskin argued in a recent article. Increasing team buy-in will make for a better partnership, and that could in turn lead to a more stable league. But there are benefits to a relegation model as well, especially for a nascent organization like the LCS. Some of the concerns over the relegation model are overblown. And a franchise model may not even get at the real issue, which is how revenues are generated and shared. It’s dangerous to look at franchising in esports without considering the real downsides to relegations, because there really aren’t any.

What’s the harm?

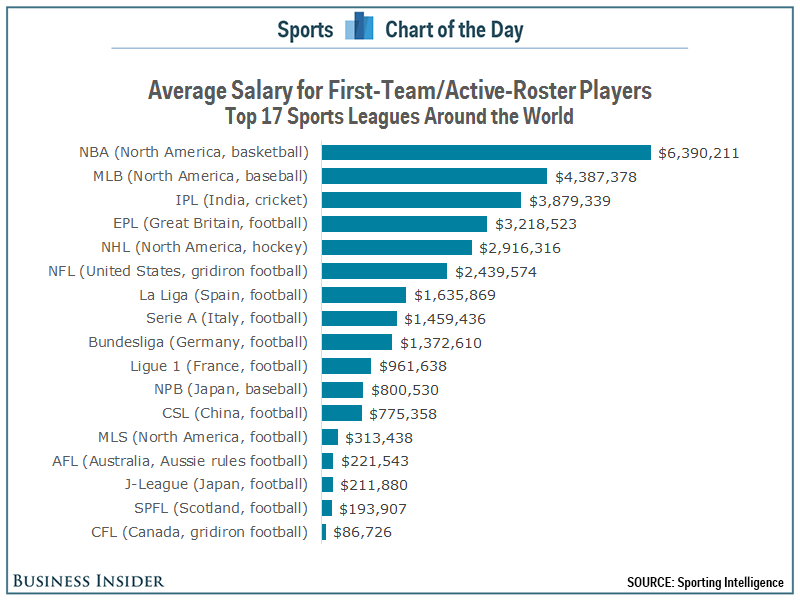

The primary arguments against relegation attribute the system to decreasing the health of the competitive environment. Things like player wage inflation, a disparity in competitiveness, and a growing economic bubble, have all been tied to this model. But when examined point-by-point, the arguments fall flat. Take wage inflation, for instance. There is no doubt that inflation has occurred in League’s player wages over the last several years. While public wage data is scarce, we know from surveys and other sources that wages have been on a steady climb and now top six figures in the NA LCS. But it is hard to argue this is the cause of relegation. According to a report from Business Insider, there appears to be little correlation between league structure and average player salaries:

In fact, wage inflation is equally a part of a franchised league as one that features relegation:

Of course, these examples simplify things greatly and ignore other structural factors. But the key is that those factors have little to do with the relegation vs. franchising debate. Wages are set based on simple economic principles including scarcity, demand, supply, and obstructions to the free flow of player services. It’s easy to see how these factors can lead to vastly different outcomes when holding the overall league structure constant. For example, much has been written about the salary disparity between the NBA and the NFL—both franchise systems. There are complicated issues at play, most notably the fact that there are 3.5 NFL players for every NBA player. But other factors include the failed NFL strike in the 1980’s, which is still having repercussions on free agency salaries today. Compare that to what’s happening in esports. While the overall prize pools and stipend payments from Riot have grown, the largest impact on player salaries in the recent period has been the influx of venture capital and other investors that have injected cash into the League ecosystem. This inflation has shifted the demand curve, creating a naturally higher price point for talent. In a vlog posted in 2016, former LCS team owner Former owner Christopher “Montecristo” Mykles said that VC investment in 2016 tripled player salaries. There just isn’t any data that show that a relegated system inflates player salaries beyond where simple economics indicate they should be.

Relegation’s effect on team value

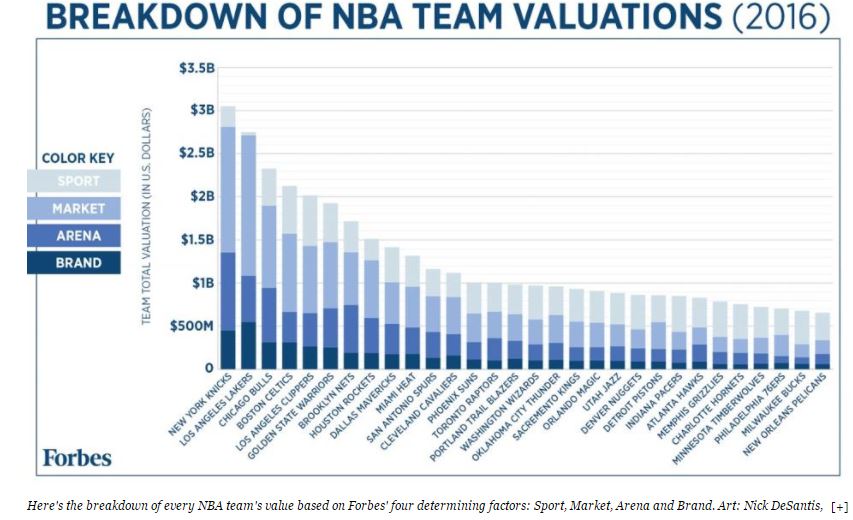

Another argument against relegation is that it negatively affects competitive balance due to its influence on team value. The thinking is that lower-ranked teams that face relegation are less likely to draw significant sponsorship revenues (lower brand value), which means they also have fewer resources with which to field more competitive rosters. The result is a slippery slope where teams get worse over time until they are relegated, increasing the gap between good and bad teams. The hypothesis is that, in a non-relegated model, economic earnings are spread more evenly across teams, regardless of competitive nature. A close look at the data doesn’t support this theory. On the surface, it may look as though franchised leagues produce more competitive parity regardless of franchise value. A Forbes survey of NBA teams from 2016 indicates as much, as strong teams like the San Antonio Spurs exist with a middling brand value. But look closely at this graph from the article:

Brand valuation, the darkest blue, makes up for a minor percentage of the total valuation for each team. And it isn’t correlated to team success because it isn’t supposed to be. Instead, valuations are predominately driven by market factors, which are based on the geographic markets in which teams operate. These economics are similar to those in European soccer, the closest comparison of a relegated structure. In the English Premier League, valuations are driven largely by teams located in large, important communities like London, Manchester, and Liverpool. The same is true in the La Liga, with teams from Barcelona and Madrid. Manchester United, a successful franchise, dominates the EPL valuation table. But when combining teams by relative geography, London teams (Chelsea, Arsenal, Tottenham, West Ham, and Crystal Palace) surpass the Manchester teams (United and City) in combined value. Finally, United didn’t become a phenomenon on the back of its finances, but rather based on the results of managers like Matt Busby, who took a team on the brink of bankruptcy to the European title, and Alex Ferguson, who built it into a powerhouse before the advent of cable TV money. The point is, brand valuations are driven by similar factors regardless of league structure. And geography-based market concerns don’t exist in the present NA LCS, where teams are based in the same market (Los Angeles). They may not even persist if the LPL switches to a regional model, since League is predominately watched via online streaming platforms that aren’t region-specific.

Does brand value drive competitive success?

With greater economic wherewithal comes greater team success. As shown in the United example, the causation is not certain. Furthermore, data does not conclusively prove that this correlation is exacerbated by a relegation structure. Much is made of the fact that only six teams have won the Premier League since its inception in 1992. What about the 10 teams that have won every NBA championship since 1984? Or the fact that fact that 11 NBA teams in the top half of the valuation table have won a title, compared to two in the bottom half? That even ignores other North American phenomenons like the draft lottery and the lack of free agency that evenly distributes player assets in a wholly uneconomic manner. There is greater championship parity in franchised leagues like the NFL and MLB. But parity in these leagues is largely driven by their one-off, luck-based playoffs systems. Unlike basketball and soccer, a playoff system in football and baseball mean the best teams often don’t win the championship. The data show that sometimes, it’s better to be lucky than good. This is no different than European soccer, where the staid league play leads to predictable results while knockout, open playoff-style cups lead to more unpredictable results and greater parity. Since 1984, 25 unique teams have competed in the FA Cup championship, a remarkable trend of diversity, compared to only 11 winners and runners-up in the Premier League and its antecedents. Over the same time period, La Liga has had just 8 teams contend for its championship compared to 18 in the Copa del Rey, Spain’s knockout tournament. The league format matters more than the economic structure. Those wanting competitive balance should favor a equal revenue distribution regardless of market affiliation and a playoff system that encourages variance—not a franchised league.

The other side of competitive balance

All the talk about competitive balance at the top of the ladder ignores another grim reality of franchised leagues: what happens at the bottom. First, let’s ignore the draft system in American sports, which encourages tanking in certain sports. This archaic system is a byproduct of several factors, including collegiate athletics, that have nothing to do with esports. But even in leagues where tanking is anathema, bad teams continually hang on at the bottom, feeding off revenue sharing and the success of the best teams. The NFL’s Cleveland Browns have been a disaster since being re-established, marred by mismanagement on both the football and business sides of the operation. Relegating that team would leave Cleveland fans, who’ve already lived through Art Modell moving their team out of town, in a lurch. But as mentioned previously, esports are liberated from these regional shackles and fans of relegated teams can more easily find new ones. Browns-level ineptitude should be prevented by relegations. Bad teams are eliminated and replaced with those that have proven to manage their resources better. And there are teams that are not run smoothly. In recent interviews, team owners like Noah Whinston of Immortals and Andy Dinh of TSM have explained in different ways how other teams are failing at tasks like fan engagement and following visa rules. With only 10 teams in the LCS, relegations currently have an outsized impact on the league table. After all, Europe just saw 20 percent of its teams relegated, even after the promotion tournament was restructured to favor existing LCS teams. With untenable economics in the Challenger Series, this has a big impact on league stability. But the goal of relegations should be to promote better, more stable teams into the league that would be less likely to be relegated in the future. As the league grows, the impact of relegations will decline. Riot’s official releases on the matter indicate that it is still deciding which partners are best for the long-term evolution of the sport. This is especially important—having the right investors at the start of any venture is key to successful results.

The problem of revenue streams

“Whether you have franchising or relegations, this [revenue sharing] is the thing that needs to change.” — Montecristo

When most people think of the unstable current environment in League esports, they’re largely referring to the risk versus return dynamic organizations currently face. It can cost over $1 million per year to run a successful LCS team with the constant threat of relegations hanging over the organization. That is the risk. The return is the player stipend, the current LCS prize pool of $200,000 per split, along with larger prize pools for the teams that compete in international events (the Worlds 2016 prize pool topped $5 million). The risk aspect is what’s being discussed in the relegation vs. franchising framework, but the reward aspect is more important. Noticeably missing from the reward formula is revenue sharing. This is—and should be—the focal point of creating a new league structure, not franchising. Montecristo indicated that sponsorship revenue made up approximately 95 percent of his team’s revenue in 2016. This is both inefficient—teams can’t collectively bargain using the combined star power of the entire league—and disjointed, as teams fight for competing sponsors. Montecristo made it clear in his vlog that “whether you have franchising or relegations, this [revenue sharing] is the thing that needs to change.” Instead Riot’s goal should be to produce a broadcast worthy of increased monetization. In fact, it’s already taken steps along this road by signing a deal with BAMTech to advance the broadcast of their games. Note that monetizing the broadcast and sharing revenue with the teams does not require franchising. A parallel can be drawn to the EPL’s 1992 deal with BSkyB to monetize TV coverage of its games via broadcast on a paid channel. That deal succeeded because of the quality of English football. And it set the tone for the rapid expansion of the league over the next two decades. Notably, it was not hampered by the EPL’s relegation system. The key question for Riot and the LCS teams is how to provide a good product that fans, players, broadcasters, and investors can all benefit from. In this process, it’s important to separate the revenue share issue from the question of franchising. The relegation/franchising system may have a role to play in creating a more compelling product. It’s possible that having a stable league with known teams will lead to better economics for all. But the opposite is also highly likely, especially in light of the arguments made above. A relegation system promotes stability by ensuring the quality of the league from top to bottom, especially while the league is new and best practices are still being developed. For the players, it allows them an additional avenue into the LCS beyond trusting that the worst organizations will succeed at scouting and coaching.

The immaturity issue

Finally, it should be acknowledged that there are key differences between the relegation system in soccer and the franchise system in American sports. European soccer was founded on a club system, and competition between clubs, big and small, would have continued regardless of the establishment of the EPL, La Liga, and Bundesliga. Much has been made of how EPL side Bournemouth competed for 85 years in England’s lower divisions before being promoted to the big leagues. That soccer is an established, mature sport in Europe is what makes this possible. Esports is in nearly the opposite state. In fact, it’s such a nascent industry that one question may supersede all others: Is Riot even the right organization to be running this league? Throughout its history, Riot has chosen to exert tremendous control of the production of League esports. This is a key distinction between esports and traditional sports. Historically, Riot’s production value has been through the roof. But it’s possible that future growth in esports requires a double shot of stability: reward via broadcast rights and revenue sharing, and risk mitigation via the abolishment of relegations. Then again, too much growth in investment, too soon, could be detrimental for the long-term stability of the league by introducing unstable partners with varying motivations. A franchise model would shift power dramatically from the publisher and sponsors to the teams and investors, though it remains to be seen what the ultimate level of influence Riot will retain in League esports. And the shift toward owner power would likely lead to declining player power—if not in wages, then in freedom. There are important consequences to a tectonic shift like this. It’s important to note that these decisions need not to be made hastily, nor all at once. There are ways to structure relegations to be less damning for teams that drop out, such as via parachute payments (continuing payments to recently relegated teams to soften the financial blow), an improved challenger scene, or other methods. Or perhaps, instead of franchising, the promotion tournament is suspended for a certain time period, or until certain milestones are met, all while the Challenger scene is revamped with increased support from LCS teams. There are a lot of ideas in the middle between relegations and franchising. The key? All of these require more maturity and stability in esports regardless of league structure. Things in esports change fast. It’s hard to create something that lasts, and it’s possible that Riot and its team partners have a short window to set a lasting foundation. But decisions need to be made with the whole picture in mind. The link between a franchised league and a healthier competitive environment is at best unproven. There may be better ways to create the ideal esports league than to pursue a franchised model.